Can We Agree on the Philippines' National Dish?

An overview on Ramos' "Dila at Bandila" (with exclusive insights from the author) and a discussion on the endless debate for the Philippines' national dish.

While some will vouch for Adobo and Sinigang for our national dish, others will argue for our lesser known dishes, such as Sisig or even Kare Kare, which are equally as valuable to consider.

To claim a dish as a national dish would need to go beyond the very surface level criteria of popularity, however. While a dish may receive widespread praise, if it fails to resonate as an accurate representation of its people, it would lack the deeper cultural and emotional significance that truly defines a national dish.

Ige Ramos touches on this matter in his book “Dila at Bandila”. He opens up the discussion to the realm of Filipino cuisine, navigating its brief history, influences, and definitions of what is considered Filipino food.

While an easy question to pose, choosing a single dish comes with historical and political implications.

I’ve also had the privilege to connect with Ige Ramos the other day to briefly discuss modern insights towards his book and thoughts on the direction of Filipino food for the future.

The Difficulty in Finding a “True” National Dish

First, I believe three key barriers are what prevents us from unanimously agreeing on one single dish.

The Philippines’ Diversity

Let’s consider the major fact that the Philippines is an archipelago comprised of over 7,000 islands. Each region is uniquely rich and diverse, which can work as a double-edged sword.

We have the privilege to enjoy hundreds of different variations of the same dish, though this same regional diversity can lead to underrepresentation of our people if their dishes aren’t considered.

We often associate Filipino culture with the most popular foods from our well-known regions like Metro Manila, though this focus can often overshadow and sideline our equally as significant dishes from other regions.

A single dish may become be an oversimplification of the complexity of our cuisine. It would undermine the vastness and rich culinary heritage that the Philippines can offer.

The Line Between Pre-Colonial and Post-Colonial Cuisine

Second, how should we define authentic Filipino food? Do we define a true Filipino dish as one cooked by our Indigenous ancestors? Or do we see it as reflecting our multicultural heritage in a post-colonial era?

If the national dish were to be based solely on pre-colonial criteria, perhaps we can turn towards dishes traditionally cooked as how our ancestors would have done.

Dishes primarily boiled in palayoks or grilled over live flames would take precedence. Foods largely seasoned with vinegar and salt would be the main flavor profiles as to reflect the popular preservation methods of the Indigenous Filipinos.

Alternatively, if our dish were to be defined as a culmination of centuries of trade and colonization, perhaps we can then open the discussion to dishes that stood the test of time and continued to evolve amidst history.

We can then choose from a wider variety of dishes that utilizes newer techniques taught by the Spaniards (such as sautéing), and even include, not only local produce, but also foreign ingredients that reflects our rich trading history with other countries.

Family Bias

Finally, beyond the regional variants, we also have our household variants.

Something as simple as Adobo, for instance, can further trigger the conversation of “That’s not how my Lola makes it”. No two adobo from different households will ever taste or look the same.

Some may prefer a saucy, soupy Adobo, while others prefer theirs dry. But wait, does the recipe include sugar or no sugar? Should we crush or mince the garlic? Is the black pepper supposed to be cracked or kept whole?

Like with most Filipino dishes, a lack of standardization isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It makes our cuisine unique and allows it to grow beyond traditional methods.

Unfortunately, this also makes it difficult to present a singular version as the sole, national dish.

The flexibility of our cuisine to evolve, though it reflects our great adaptability, poses as a challenge in determining and pinpointing a single, enduring national dish as a result.

How Should a National Dish be Defined?

Many would consider Adobo as the unofficial national dish of the Philippines due to its widespread recognition and deep cultural significance.

However, what factors would truly define a national dish? Should it be based on popularity, history, accessibility, cultural symbolism, or maybe a mixture of all of them?

If our national dish were to be one that reflects our history, it should be a food that carries the story of our unique historical and cultural heritage.

Perhaps Adobo does fit that category. It has its roots in pre-colonial times, eventually integrating the use of soy sauce after contact with the Chinese, its name given during the Spanish colonization, and it continues to be a staple in many Filipino households to this day.

Alternatively, if the dish were to be one that reflects accessibility, maybe we should choose a dish that every Filipino can easily make, consume, and afford. A dish that transcends social class and location can be a powerful criteria to determine our national food.

Ramos, in his book, proposed the idea that Suman, the sticky, glutinous rice dish wrapped in banana leaf, should undoubtedly be our national dish.

Suman is neutral, for it can be consumed by all regardless of religion or faith. It’s greatly linked to Philippine life, easily consumed as a casual breakfast item, or more significantly during ceremonies and events. Suman is also made of rice and banana leaf which can be found in abundance in the Philippines.

Lastly, if we decided to choose a national dish on the criteria of cultural symbolism, we should choose a dish that unifies us under a common collective identity.

Perhaps then, we could select a dish that symbolizes the Filipino’s resourcefulness, such as Sinigang.

Sinigang can be made with many proteins such as pork, beef, shrimp, or fish. It can also just plainly be comprised of vegetables.

While the core identity of Sinigang remains in its signature sourness, the dish also adapts to its environment. Tamarind may be the most common souring agent, though other regions may utilize green mango, unripe guava, or alibangbang leaves as these are what’s more commonly accessible in their area.

Sinigang not only suits the flavor palate of the Philippines, but it also represents the very being of the Filipino’s collective adaptability and resourcefulness, whether they’re in the mainland or abroad.

What If We Don’t Need Just One?

Even though Adobo is widely regarded as the de facto national dish, we all know that the Philippines is so much more than just Adobo.

If we did officially make this our national dish, I think we should vaguely call it “Adobo” and leave it at that.

Leave it to the people to interpret what that version of Adobo is. Whether it’s made with chicken or pork, uses soy sauce or none, or takes on a more regional route by using atsuete, coconut, or turmeric.

Adobo, at its core, will always be a reflection of the Filipino who makes it.

Rather than debating on a single dish, we should instead uplift the entirety of Filipino cuisine as a whole through storytelling, sharing traditional recipes, and continuously supporting Filipino businesses who work tirelessly to promote our culture.

Q&A With Author Ige Ramos

Before wrapping this up, I wanted to include this quick Q&A I did with the author, Ige.

While the main focus of this newsletter was navigating the discussion for the national dish, I wanted to ask Ige questions that went beyond this topic to gather a more holistic appreciation towards his book and thinking process in the context of our rapidly changing Filipino food scene.

Your book weaves culinary critique and history into a single narrative. Which Filipino writers, thinkers, or chefs helped shape your perspective as a writer?

I've certainly stood on the shoulders of some remarkable individuals. Their words, ideas, and passion have undoubtedly seasoned my own writing.

Firstly, I must mention the giants of our historical and cultural narratives. The meticulous research and evocative prose of historians like Ambeth Ocampo and Felice Sta. Maria have been a constant source of inspiration. Their ability to weave compelling stories from historical fragments, much like I try to do with culinary history, has taught me the importance of digging deep and presenting the past in an engaging manner. Their works reminds me that every dish has a story waiting to be unearthed.

Then there are the literary voices that have shaped my understanding of Filipino identity and experience. While not strictly culinary writers, the works of Nick Joaquin, with his rich descriptions of Manila and his exploration of our cultural psyche, have deeply influenced my appreciation for the context in which our food traditions evolved. His evocative language and sense of place resonate with my own desire to paint a vivid picture of Filipino culinary landscapes.

In the realm of food itself, while perhaps not always in the formal sense of culinary critique, the passionate documentation and promotion of regional cuisines by figures like the late Doreen Gamboa Fernandez and Gilda Cordero Fernando have been incredibly influential. Their dedication to exploring the nuances of Filipino flavors and respect for local ingredients set a benchmark for thoughtful engagement with our culinary heritage. They showed us that food is not just sustenance but a vital expression of our culture and identity.

More contemporary voices, chefs who are pushing the boundaries while honoring tradition, also play a role. Having worked with him in collaborating with his publications as a book designer and co-writer, observing the thoughtful approaches of chefs like Claude Tayag, who champions not only Kapampangan but also the cuisines of the Philippines with both reverence and innovation, and others who are exploring the diverse tapestry of Filipino regional cooking, informs my own understanding and appreciation. Their dedication to quality and their commitment to showcasing the best of Filipino ingredients inspire me to write with similar passion and respect.

So, it's a tapestry woven from historians who illuminate our past, literary figures who capture our spirit, and culinary champions who celebrate our flavors. They have all, in their own way, helped me to see the Filipino table not just as a place of nourishment, but as a vibrant stage where history, culture, and identity converge.

Dila at Bandila is still recent, but had you decided to write your book today, with the Filipino food scene continuing to change rapidly, what would you include now that wasn’t in the original? Or would your thoughts remain the same?

Even as I hold a copy in my hands today here in Pasay, I can feel the currents of change swirling around the Filipino food scene. Had I sat down to write it anew, knowing what I know now, several new layers would undoubtedly find their way into the narrative.

Firstly, the resurgence and evolution of regional cuisines has become even more pronounced. While I touched upon themes like “crops of oppression,” “debunking adobo as a national dish,” and the “diversity of our culinary landscape” in the book, the past few years have seen an explosion of interest and innovation within specific regions. We're seeing more chefs and home cooks championing heirloom ingredients and forgotten dishes from places like Mindanao, the Cordilleras, and the Visayas with a newfound confidence and sophistication. I would certainly dedicate more space to exploring these deeper regional nuances and the individuals driving this exciting movement.

Secondly, the globalization and reinterpretation of Filipino food have accelerated. More Filipino chefs are making waves internationally, not just by replicating traditional dishes but by creatively fusing Filipino flavors with other culinary traditions. This dialogue between the local and the global is a fascinating development. I would delve deeper into this phenomenon, examining how Filipino cuisine is being understood and adapted on the world stage and how this, in turn, influences our own understanding of what it means to be "Filipino" on a plate.

Thirdly, the rise of social media and digital platforms has profoundly impacted how we discover, discuss, and consume Filipino food. Food bloggers, Instagrammers, and online communities have become powerful forces in shaping culinary trends and raising awareness about both established and emerging food businesses. This digital landscape has created a more democratized space for culinary voices, and I would certainly explore its influence on our food culture and how it's shaping the narrative around Filipino cuisine.

Fourthly, I would likely spend more time examining the sustainability and ethical sourcing of ingredients. There's a growing awareness and concern among both consumers and producers about where our food comes from and the impact it has on the environment and local communities. This is a crucial conversation that is increasingly shaping culinary choices, and I would want to weave this thread more explicitly into the narrative.

Finally, the intergenerational dialogue within Filipino food is becoming richer. We see younger generations embracing and reinterpreting ancestral recipes while also pushing boundaries with modern techniques. This interplay between tradition and innovation is vital for the continued evolution of our cuisine, and I would explore this dynamic with greater depth.

While the core themes of Dila at Bandila—the intertwining of our history, culture, and food—would remain central, the lens through which I examine them would be sharper, reflecting the dynamic and rapidly evolving Filipino food scene of today. The conversation has become even more vibrant, more diverse, and more globally connected, and my book would need to capture that exciting energy.

With Filipino cuisine evolving in a more Western direction through the diaspora, how would you perceive the balance between retaining authenticity and innovation in representing our food globally?

As a keen observer of our evolving gastronomic landscape, I see this "Western direction" in the diaspora not necessarily as a deviation, but rather as another layer in the complex history of Filipino food itself.

Let's first consider what we mean by "authenticity." Is it a rigid adherence to recipes from a specific era? Or is it the spirit and intention behind the flavors, the connection to our cultural memory and ingredients, even when expressed through different techniques or with locally available substitutes? I lean towards the latter. Our cuisine has always been one of adaptation and fusion, influenced by trade, colonization, and migration. To insist on a static, unchanging definition of authenticity would be to ignore the very nature of our culinary journey.

The diaspora, in its own way, is a continuation of this historical process. Filipinos abroad, often missing the specific ingredients of home, will naturally adapt recipes using what is available. They might incorporate Western techniques they've learned or cater to the palates of their adopted communities. This isn't necessarily a dilution of our food; it can be a creative reimagining, a way to keep the flame of Filipino flavors burning in new lands. Think of it as a culinary balikbayan—bringing familiar tastes into a new context.

However, the crucial balance lies in ensuring that this innovation remains rooted in the essence of Filipino flavors and culinary principles. The sarap—that unique deliciousness that defines our food—should still be discernible. The balance of sweet, sour, salty, and sometimes bitter, the use of key ingredients like patis, bagoong, calamansi, and sinigang broth—these are the anchors that keep the innovation tethered to our culinary identity.

Innovation for the sake of novelty, without understanding or respecting the foundational flavors, risks losing that connection to our heritage. It becomes just another dish with a Filipino-sounding name, devoid of the soul of our cuisine.

Therefore, I believe the responsibility lies with those representing Filipino food globally—whether they are chefs in Michelin-starred restaurants or home cooks sharing their adobo with neighbors. The key is to have a deep understanding of our culinary history and the principles behind our dishes. Innovation should be informed by this knowledge, a respectful evolution rather than a radical departure.

We can celebrate the creativity of a Filipino chef in New York who makes a kinilaw with local seafood and a citrus dressing inspired by calamansi if the fundamental tartness and freshness of kinilaw are present. We can appreciate the ube desserts that have taken the world by storm, as long as the distinct flavor of the purple yam shines through.

Ultimately, the representation of Filipino food globally should be a dynamic conversation between tradition and innovation. It should honor our past while embracing the possibilities of the present and the future. It's about carrying the spirit of our luto—our way of cooking and sharing food with love and generosity—across borders, even if the ingredients or techniques take on a slightly different form. The heart, the lasa, must remain authentically Filipino.

This is an excerpt and ideas from my new book with a long title:

Eat Filipino food, not for the history, because we’re not sure what is authentic.

Eat Filipino food, not for the culture, because we’re not exotic enough.

Eat Filipino food because everything you know about it is wrong.

Bukambibig/Word of Mouth by Ige Ramos, not a Filipino Cookbook.

To give Dila at Bandila a read, you can purchase it online here.

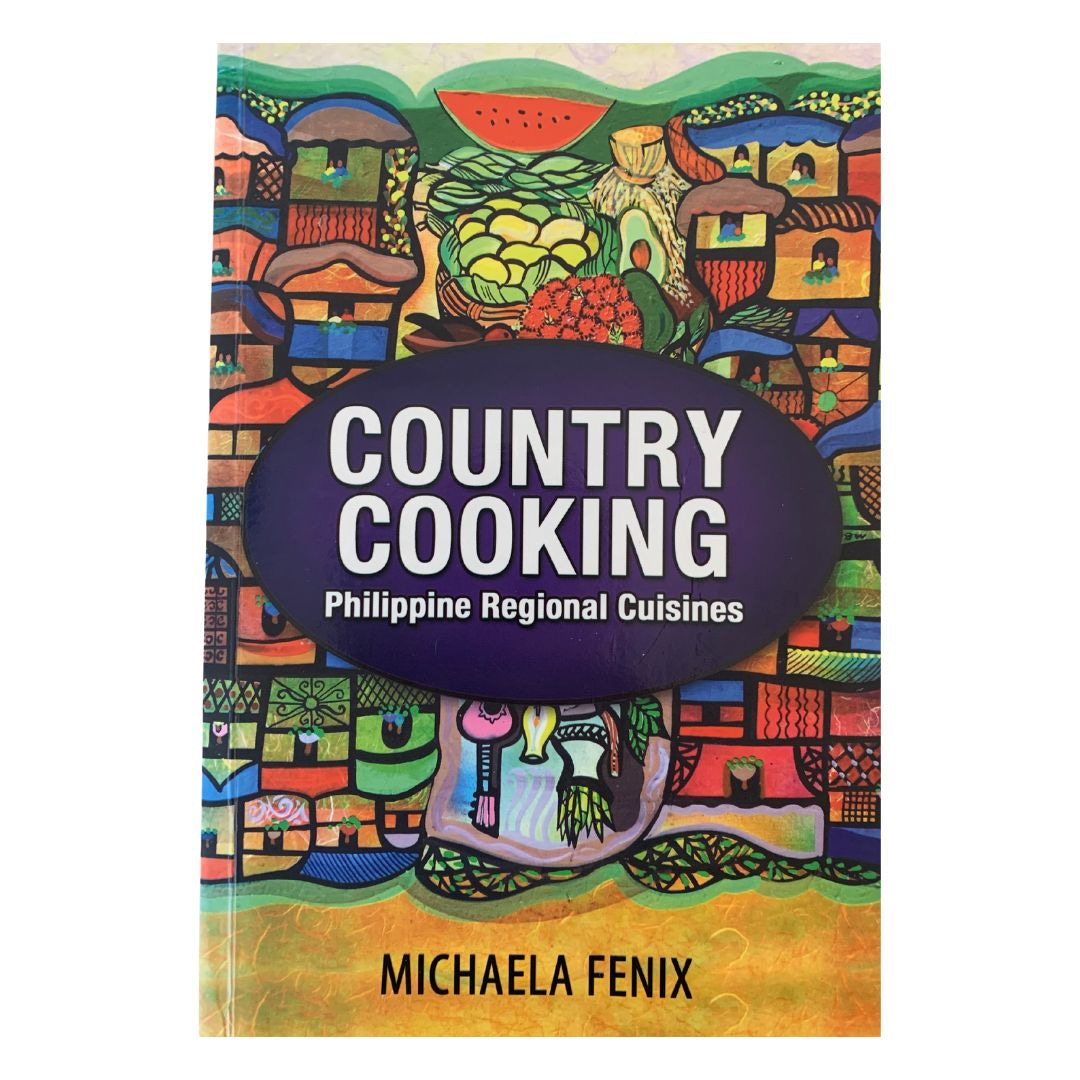

And the book we’re currently reading for the month of April is…

In this book, Fenix takes us through the various regional cuisines of the Philippines, some of which are usually overshadowed by our more mainstream culture.

It's harder to find physical copies, but the kindle and digital versions are also available online.

Feel free to comment, tag, or DM me any of your thoughts -I love discussing everything related to Filipino culture and food.

Happy reading, until the next deep-dive.

There's no one Filipino dish that can be made "national" because there are regional specialities and each are unique and equally worthy! Although I love sinigang and inasal and kansi and sisig, I am biased with adobo. Guess that's my vote. I am adobo down under after all 😆

I’ll eat ‘em all!!